By Violeta Aybar-Maki

February 6, 2022

One might be tempted to consider Les Heures d’Etienne Chevalier as a mere glorification of its patron –in the manner of other texts of the same kind. Throughout this illuminated manuscript we find the inscriptions “Maistre Etienne Chevalier” as well as the initials E. C. in almost every page. It is clearly the way in which men like Chevalier sought to compensate for the reality of their bourgeois origins and, in following the example set by French monarchs, it will become a tool for legitimizing his authority, also remaining as a testament to his life. But what the forty-seven surviving pages of this manuscript show is the performance of a man working at the height of his artistic career. The historical importance of these miniatures goes beyond the display of pride of Etienne Chevalier and rests upon the artistic achievement of Jean Fouquet. The miniatures in this book of hours clearly demonstrate how his technical mastery and his stylistic approach drink from Italian and Flemish sources, but always in keeping with French artistic traditions and contemporary French life.

Jean Fouquet was born in Tours between 1415 and 1420, during very difficult political and economic times. The French territory was divided and torn to half its size; Paris was besieged by enemy forces; and trade and commerce was in decline. However, the France of Fouquet will also experience great moments of transformation and progress under the reigns of Charles VII, to whom the artist pledged his loyalty and admiration, and Louis XI. In many ways Fouquet was deeply involved in the life of his time, and the Hours of Etienne Chevalier is not deprived of political messages. For example, his illustration of the Adoration of the Magi (fig. 1) depicts a kneeling Charles VII taking the place of the first magi and offering frankincense and myrrh to the Virgin and the Holy Child. This type of homage was not unique in its kind. However, important elements operating within the picture plane enhance the narrative aspect of the miniature in a way only Fouquet could achieve at the time. In the foreground, the Holy Family and the king form a unity, in the manner of a triangular composition; the cloth of honor upon which the king kneels, and the Virgin’s dress are rendered in the same deep tone of blue, thus establishing a connection with Christ. The scene becomes more poignant by what is taking place in the background; the destruction of Sodom adapted to a contemporary theme –the victory of the French army against the English enemy.

Figure 1 Figure 2

Much comes to light while unpacking one of these miniature illustrations, bound to be no larger than an adult hand. They reveal a great deal of information about the artist –not just regarding his artistic abilities, but what his influences are, as well as the political and cultural landscape of France. The details of Fouquet’s obscure birth, however, are quite uncertain, but it is well known that he became an apprentice in Paris, probably in the workshop of Haincelin de Haguenau, before his journey through Italy. These aspects of his artistic education are important because they will equally permeate throughout his work, and they are most evident in the Chevalier Book of Hours. For example, his treatment of iconography indicates his knowledge of Italian themes, as well as French. In the Birth of St. John the Baptist (fig. 2) the Virgin, sitting close to Zacharias, holds the child waiting for the servants to prepare his first bath; apparently Mary had remained with Elizabeth since the Visitation. This is an Italian theme depicted in a French setting –a room with white-washed walls in what looked like a middle-class home. On the other hand, in The Coronation of the Virgin (fig. 4) and in the Trinity in Glory (fig.3) Fouquet, follows the French iconographic tradition by depicting the Holy Trinity as three identical men sitting on a tripartite throne.

The miniatures discussed above also offer an example of the artist’s thoughtful use of architectural vocabulary in order to convey a specific message or feeling. If the calm scene in the Coronation of the Virgin requires a classical throne with Corinthian pilasters, the scene depicted in the Trinity in Glory showcases a Gothic throne in the midst of a grand spectacle of light. This aspect of his work shows his ability to operate within multiple dimensions, for it is possible to see the artist’s mind at work. Fouquet’s stylistic choices correspond with the narrative, and at the same time they provide hints to the influential forces behind them. His interest in depicting architecture might have been learnt in his apprenticeship in Paris, but what Les Heures d’Etienne Chevalier brings to light is the importance of his journey through Italy, particularly in the development of a mature artistic identity within the French tradition.

Figure 3 Figure 4

The juxtaposition of Gothic and Renaissance architectural elements, along with recognizable landscapes from Tours and from Paris might also be nourished with a Tuscan atmosphere. In St. Stephen and Etienne Chevalier before the Virgin (figs.5 & 6), for example, Chevalier and his patron saint are shown kneeling in front of the Virgin along with a group of singing angels. For this scene Fouquet placed these figures in what looks like a Tuscan palace, we see here the same golden pilasters of the Coronation. However, the Virgin is depicted enthroned within a Gothic portal, a choice made perhaps in relation to the concept of sacred architecture, meant to determine what belongs to the earth and what belongs to the heavens. Even more fascinating is the setting in St. Veranus Curing the Insane (fig. 7) where the saint performs the miracle inside a carefully detailed and architecturally precise north aisle of the Cathedral of Paris. Moreover, in the Descent of the Holy Ghost Upon the Faithful (fig. 8) Fouquet illustrates the façade of the cathedral in the background, along with a view of the city of Paris. In unpacking this image in particular one could easily find two important aspects of his work. First, he is offering a political allusion, following up on the theme we saw in the Adoration of the Magi –a tribute to King Charles VII and the defeat of the English enemy, here represented by a group of demons hovering over Paris. Finally, there is the aspect of how important these miniatures can be in documenting, in the manner of photographic evidence, how a building might have looked like in a given historical moment, as well as providing the topographical view of a specific landscape.

Most unprecedented was perhaps his approach to composition and depth, as well as his classical treatment of the human figure. These lessons were learnt in Italy, probably from seeing Masaccio’s frescoes in San Clemente, Uccello’s works in Florence and Jacopo Bellini’s in Venice:

“What Fouquet brought to France was the discovery of a new construction of the picture space. Apparently, he did not acquire theoretical knowledge of Italy’s new scientific methods, for his pictures do not conform even to the elementary law of the one and only vanishing point. He learnt entirely from practice and never completely penetrated the secret. But what he had grasped was enough to build up a new artistic order in his own imagery.”

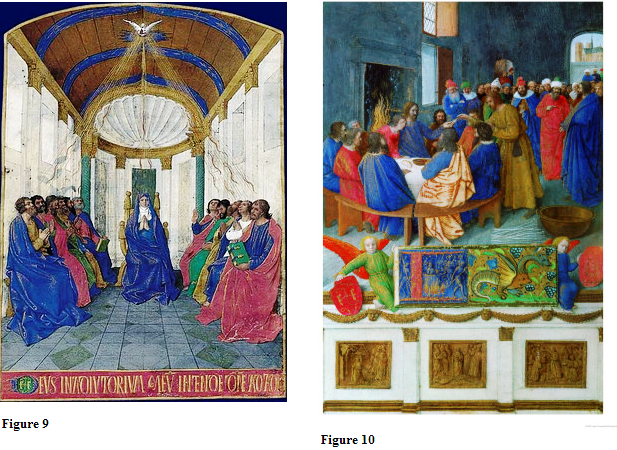

Fouquet’s miniatures in the Chevalier Hours reveal that whatever his approach to perspective might have been, not completely “penetrating” its secret did not deprived his construction of space from clarity and harmony. His use of spatial depth rests heavily in the arrangement of figures and objects in the picture plane. For example, in the Pentecost (fig. 9) we see a distinct recession that heightens the perspective view of the interior, further emphasized by the diagonal arrangement of figures along the walls. It becomes evident that both figures and walls form a clear indivisible unit, and every element is placed at an angle with the picture surface creating a sense of order and harmony. Also, Fouquet’s mastery in matters of composition can be seen in a number of the miniatures that are organized in two or three consecutive picture planes.

In the Birth of St. John the Baptist the picture plane is divided in two. In the foreground, a placard with the initials of Etienne Chevalier is placed in between the scene of the birth and the two-winged figures that appear to be underneath. This illusionistic scheme helps the scene recede in space, since our eyes locate the figures behind the placard due to its casting shadow. Fouquet is clearly channeling the trompe l’oeil frescoes by the Italian artists mentioned above. But there will also be an important source of French origin behind the execution of such characteristic arrangements –Medieval Theatre, more specifically the Mystery Plays. These theatrical representations were of a religious nature and were represented as a succession of tableaux showcasing very little movement or action. One could agree with the fact that Fouquet drew inspiration from these plays, due to the religious nature of his paintings –themes and stories mostly taken from the Bible and the Golden Legend. However, it was during his lifetime that a new type of play developed around themes of a social and political nature –the moralities and the farces, and perhaps their ethical quality might be found in the artist’s liturgical representations as well.

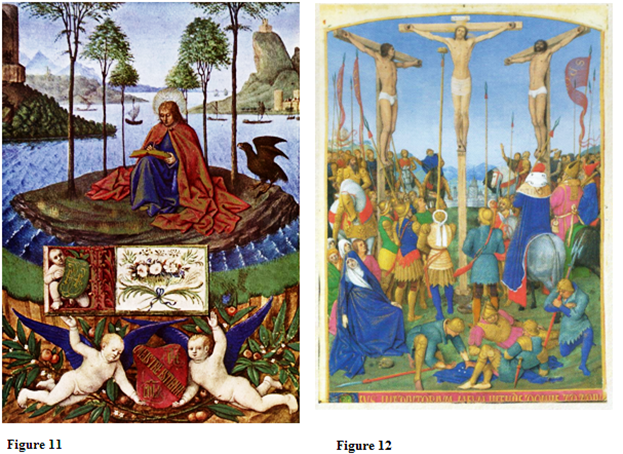

“…Fouquet’s emphasis upon Judas’s golden costume, his bag of gold, and his association with rich and powerful men in The Last Supper (fig. 10). The painter’s concern for ethical integrity stands in sharpest contrast to the Limbourg Brothers’ lack of just that concern –for Fouquet was a great perspectivist, and they were not. …we can see that the spirit in which Fouquet has interpreted the story owes nothing whatever to the traditions of liturgical and sacramental art and thought but is directly related to the sardonic and moralistic modalities of the new theatre. He interprets the occasion of the Last Supper as one on which a group of poor laborers and fishermen have been betrayed into the hands of rich burghers and powerful priests who have used their wealth to corrupt the man named Judas, even as the representatives of that ruling class were using their power to persecute and exploit poor but righteous men who had a better claim that they, perhaps to being called followers of Christ.”

Now it would be wise to find a common ground between the above interpretation and the fact that Fouquet enjoyed the patronage of Pope Eugene IV, King Charles VII, and high-ranking court officials of bourgeois origin like Etienne Chevalier. Whatever the case may be, the richness and unprecedented nature of his illustrations, the way in which it is possible to unpack them and discover several layers of meaning, and inspiration renders the diversity of interpretation understood.

In general, Fouquet’s treatment of space is driven by a desire to depict a world with a sense of unity. His use of archaic systems of perspective, especially circular perspective, work in terms of depth and provide his figures with a certain degree of dynamism –even though they are, for the most part, lacking in movement. In St. John on Patmos (fig. 11) we see cherubs holding the placard with Etienne Chevalier’s initials in the foreground, while the figure of the apostle appears to be behind it. Here we see how the projection of waves, along with the circular shape of the island, and the earth curving inward create an undulating illusion of movement. Even though his technique of diminution might be regarded as inconsistent, the framing trees help to focus the eye, enhancing the illusionistic force of the optical experience. This sense of movement is evident in the Trinity in Glory with the circular arrangement of static figures around a heavenly mandorla, and in Adoration of the Magi with the curvilinear disposition of the king’s personal army.

The harmonious and unifying quality of Fouquet’s compositions is further emphasized by the delicate handling of color and tone, which renders his modeling technique rather subtle. In Fouquet we find the plastic values of Flemish painting –a modeling style that relies heavily on a subtle transition from dark to light. In essence, the outcome will be uniformity of surface, and the smooth finish of textures achieved by an almost invisible brushstroke. Fouquet’s miniatures, however, present a modeling that leaves the interplay of light and dark in the open without the deprivation of subtlety and unity because it is meant for the viewer to complete the forms with their eyes. But his rendering of textures and light still reflects a Flemish sensibility. It is very probable that his interest in Flemish innovations was further stimulated after his return to France where he encounters the works of representatives of the Nordic style like André d’Ypres, Colin d’Amiens, Jacob de Listenmont and Jan van Eyck. Another possible evidence of Flemish influence in Fouquet can be seen in his Crucifixion (Fig. 12) where his arrangement of figures echoes van Eyck’s painting (Fig. 13). Here, soldiers and ecclesiastical figures are depicted surrounding the cross, while Mary –along with other female figures, is placed in the left-hand corner of the composition. Fouquet’s miniature also displays a similar view of the cityscape and topography in the background. They differ in matters of color and rhythm, if in van Eyck earthy tones predominate, in Fouquet we still see the brilliancy and clarity of tone witnessed throughout the book.

Figure 13

The importance of the Italian experience comes through in any serious analysis of Jean Fouquet. Very little is known of his early works, making before and after comparisons quite difficult. However, looking forward it is evident that he spent two to three years in Italy, mostly Rome and Florence perhaps Venice. From his time in Rome, a portrait commissioned by Pope Eugenius IV is the only one documented in records. Still, only an engraving of the painting survives, and its poor-quality shows very little of his style. What the miniatures in Les Heures d’Etienne Chevalier show is a poignant departure from the French painting of 1430 to 1440. His Italian sources –Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca will be major influential forces. In the former, we find Fouquet’s solid elegance of illumination, and figures rendered with great spiritual calm. While the latter, will communicate through a similar treatment of color –a palette that is bright and silky. The modernity of his style and the abundance of Italian references –its art, architecture and landscape, become significant factors in Fouquet’s work, and in the movement of French painting toward a full-blown Renaissance art.

But one must not forget that Jean Fouquet was, above all things, an artist of great independence. His approach shows a clear allegiance to the French painting traditions, as well as every aspect of French life. If in matters of style, we have found Flemish and Italian elements in his composition and rendering of color; we also see how everything is bathed in a subtle golden atmosphere. After all, what we are witnessing in each miniature is a narrative that will always hearken back to the cultural, political, and religious world of France. Therefore, it is only natural that Fouquet recurs to the long-standing pictorial tradition of using pure gold in modeling forms. His intention is to suggest light reflecting upon the folding cloths or to create a mystical reality embedded with the luxuriant taste of French aristocracy. This golden element is present in the Adoration of the Magi, where there is a grand display of loyalty and royal symbolism. We also witness it in Zacharias robe and in the pouring water in the Birth of St. John the Baptist. Likewise, in the dynamic circular composition of the Trinity in Glory, and the quiet atmosphere of St. John on Patmos. All these aspects combined make of this Book of Hours something more than just a book of prayers or the glorification of a wealthy patron. It is equally about the artistic achievement of its creator, and the brilliant merger of modern innovations with the symbolic power of tradition.

References

Avril, François. Jean Fouquet: Peintre et Enlumineur du XVe Siècle. Paris: Hazan, 2003.

Perls, Klaus G. Jean Fouquet. Paris: Hyperion Press, 1940

Pacht, Otto.” Jean Fouquet: A Study of His Style,” in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 4, No 1/2 (Oct., 1940 – Jan., 1942) pp. 85-102

Schaefer, Claude, et. al. “The Hours of Etienne Chevalier” by Jean Fouquet. Paris: Draeger Frères; Vilo, 1971.

Smith, Norris K. Here I Stand: Perspective from Another Point of View. NY: Columbia University Press, 1994

Wescher, Paul. Jean Fouquet and His Time. London: Pleiades Books, 1947